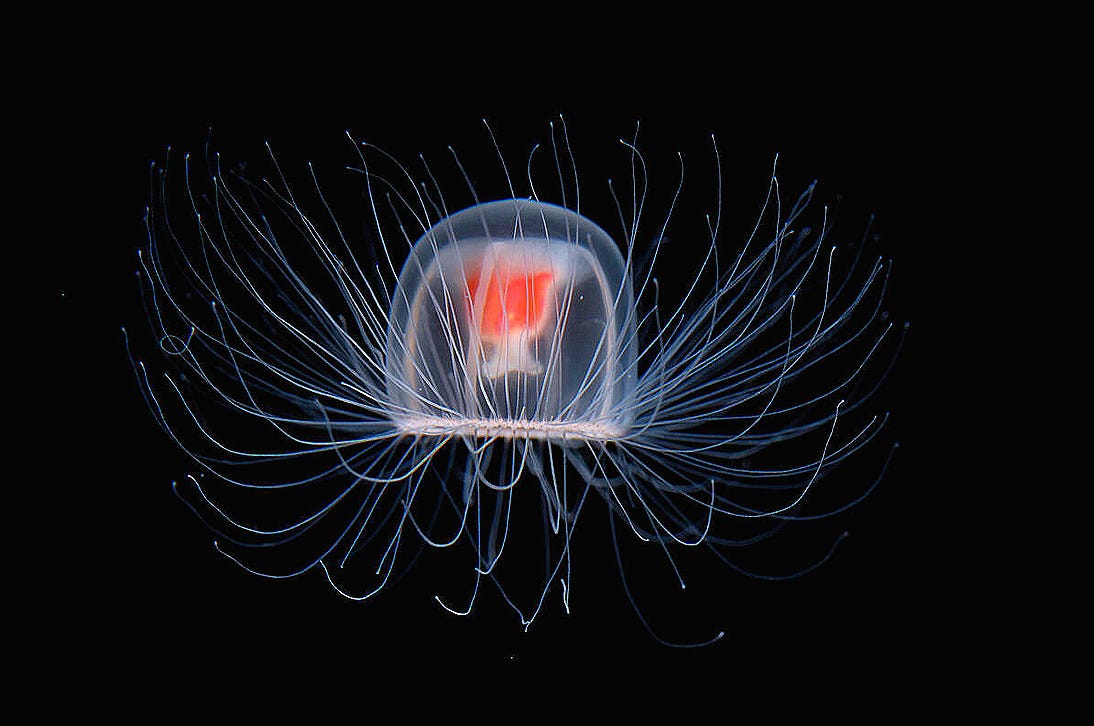

Turritopsis Dohrnii — or the immortal jellyfish, as it is popularly known — was first discovered in the Mediterranean, but is now found in various oceans around the world, thanks to transport via the ballast water of ships. It is one of the very smallest hydrozoans. The bell-like body or medusa is roughly the size of a trimmed pinky fingernail, and its rim is lined with evenly-spaced hair-like tentacles — as many as 80 or 90 in an adult. The bright red manubrium or digestive organ can be seen suspended within the medusa. Turritopsis is a free-swimming form that moves through water in slow propulsive motion, powered by rhythmic muscular contractions of the bell.

When threatened by extreme trauma like physical injury, old age, food scarcity, or adverse environmental changes such as water salinity or temperature, this tiny jellyfish has a secret for evading death. It shrinks in on itself, reabsorbing its tentacles, losing the ability to swim, and sinking down to settle as a blob on the ocean floor.

You'd think that would be the end of it for sure.

BUT hold on — what happens next is amazing. Over the next 24-36 hours, the jellyfish transforms its existing cells and reverts back to a previous state. Ensconced on the ocean floor, the larval "blob" develops into a polyp — which is the jellyfish's previous life stage. The polyp proceeds to mature and spawn a colony of new medusae.

“It’s like a butterfly turning back into a caterpillar—repeatedly,” says Dr. Shin Kubota, a Japanese biologist who has cultured Turritopsis for decades.

This process is called transdifferentiation, and it's extremely rare. It enables the jellyfish to regrow and become an entirely different form from the freely swimming jellyfish stage it previously inhabited. It then matures normally, and produces new, genetically identical medusae. Because this life cycle reversal can be repeated over and over, some like to picture an individual jellyfish as being able to live forever — which is entirely possible, as long as the individual in question escapes being eaten or killed by disease or something else.

The discovery of this rare process in Turritopsis Dohrnii has spurred interest in pursuing the idea of transdifferentiation for its potential application in human health.

“This may have implications for medicine, particularly the fields of cancer research and longevity. Peterson is now studying microRNAs (commonly denoted as miRNA), tiny strands of genetic material that regulate gene expression. MiRNA act as an on-off switch for genes. When the switch is off, the cell remains in its primitive, undifferentiated state. When the switch turns on, a cell assumes its mature form: it can become a skin cell, for instance, or a tentacle cell. MiRNA also serve a crucial role in stem-cell research — they are the mechanism by which stem cells differentiate. Most cancers, we have recently learned, are marked by alterations in miRNA. Researchers even suspect that alterations in miRNA may be a cause of cancer. If you turn a cell’s miRNA “off,” the cell loses its identity and begins acting chaotically — it becomes, in other words, cancerous.

Hydrozoans provide an ideal opportunity to study the behavior of miRNA for two reasons. They are extremely simple organisms, and miRNA are crucial to their biological development. But because there are so few hydroid experts, our understanding of these species is staggeringly incomplete.” [from a New York Times article on the aforementioned Shin Kubota — a dedicated scientist & interesting person. Also very worth watching is this short video of him singing a song — one of many he has written about jellyfish.]

While learning all of this, my thoughts kept pulling me away from the physical aspects of this fascinating little creature to the symbolism inherent in its ability to regenerate.

In biology & medicine, regeneration is understood as "the formation of new tissue or cells; the natural replacement or repair of a lost or damaged part, organ, etc.; the formation of a new individual from part of an organism, often as a form of asexual reproduction." (OED) In the jellyfish, the process is spurred by trauma. The impaired jellyfish sinks down into itself and starts its cycle of growth from its previous and most unevolved form. It regresses to near-zero & rebuilds. Could this be a physical manifestation of what emotional and/or spiritual rejuvenation might look like for us — a model?

In attempting to apply the lesson of Turritopsis to my own physical existence, my thoughts went something like this: "Sink back into Self?" Yes — that I can do, and have done! "Become a blob??" Yeah, that too. But then I get stuck. After thinking of it in solely physical terms, I found I had to extend the analogy to a nonphysical level, to look at the life-cycle, not of our physical selves, but of our emotions, our spirits, our creative hearts. Are we so unversed in living amid daily traumas that we’ve lost sight of the challenges being lived around the world and throughout history? Too used to relatively ‘comfortable’ living? It seems we need to widen the lens.

Without understanding completely what that might look like, I use as a starting point the thought that ‘sinking into myself’ could mean absorbing the downward drift toward despair as a necessary part of the cycle … the idea that regeneration is a creative process, an upward movement that only begins from a low point, where something is hurt, damaged, missing. Regeneration then assumes its true & critical role, not simply as a desperate remedy, but as inspiration or impetus — a catalyst for the change & regrowth we’re all searching for.

Turritopsis asks us to reexamine our place on the continuum — to reassess & hold on, even if it’s uncomfortable.

Marcescence (of a plant part: withering, but not falling off)

... be the oak leaf

holding fast

through winter,

the acorn cap

tight to the branch

outlined against spring blue.

I love how you used the jellyfish example to trigger an exploration of the inner self!

Miss Quiss look at this, a pocket full of jellyfish . . .